Palomino horses - especially those “golden” horses with ivory manes and tails - have probably been revered for as long as they’ve been found. They are shown on ancient tapestries, paintings and other artefacts of Europe and Asia and are found in Chinese and Japanese art from over two thousand years ago. Golden horses were the favourites of royalty and war lords.

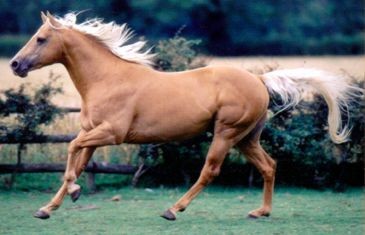

Today the “ideal” palomino (for showing purposes) should be golden with a white mane and tail, with no smuts, dapples or dark hairs. Although there are palomino “breed” societies in reality palomino is a color and not a breed. Palominos do not breed true, being able to produce both chestnut and cremello foals when bred together.

Today the “ideal” palomino (for showing purposes) should be golden with a white mane and tail, with no smuts, dapples or dark hairs. Although there are palomino “breed” societies in reality palomino is a color and not a breed. Palominos do not breed true, being able to produce both chestnut and cremello foals when bred together.

In reality palomino horses vary in shade from pale cream to a deep rich golden color. The mane and tail is usually white but may be gold and/or have dark hairs. Like chestnuts palomino horses may be affected by the sooty gene, when they display dark dapples. The effect is not unattractive but is nevertheless considered to be “incorrect” when compared with an “ideal” palomino. The coat of many palominos changes shade from cream in the winter to golden in the summer (seasonal palominos).

Pale palominos are sometimes called Isabellas, after Queen Isabella de-Bourbon of Spain, who is much remembered for pawning her jewels to fund Columbus' voyages to the “New World”. The word Palomino is itself a Spanish surname, derived from a Latin word meaning pale dove. Queen Isabella kept a hundred golden horses (but forbid her commoners to own one!). She did, however send a Palomino stallion and five mares to her Viceroy in Mexico (then called New Spain!) to perpetuate the horse in the “New World”. North America palominos originally came from the Spanish settlements, presumably descendants of Queen Isabella’s horses.

the genetics of palomino

Palomino horses have a base coat color of chestnut (i.e. of genotype ee, eaea or eea at the extension locus) and genotype C+CCr at the C locus (the cream dilution gene). The CCr allele is semi-dominant and dilutes red pigment to yellow in a single dose (i.e. in palominos). The wild-type C+ allele is effectively recessive since it needs to be homozygous for there to be no dilution of the base color.

Palomino horses have a base coat color of chestnut (i.e. of genotype ee, eaea or eea at the extension locus) and genotype C+CCr at the C locus (the cream dilution gene). The CCr allele is semi-dominant and dilutes red pigment to yellow in a single dose (i.e. in palominos). The wild-type C+ allele is effectively recessive since it needs to be homozygous for there to be no dilution of the base color.

The Gower agouti model

According to Gower (1999) the agouti locus may also have some affect on the shade of palomino. Different alleles of the agouti locus seem to be responsible for different forms of phaeomelanin (red pigment) in chestnut and palomino horses. A summary of the assumed effects of the A series on chestnut and palomino is shown in the table below. Genotypes are shown using an underscore, e.g. AA_. This represents where an allele can either be the same as the allele shown (i.e. AA in the example) or any other allele recessive to it (i.e. either At or Aa in the example, but not A+ which is dominant over all other alleles). Allele Aa is recessive to all the other alleles at the agouti locus.

| Genotype at the agouti locus | Chestnut horses | Palomino horses |

| A+_ | Light chestnut | Cream palomino |

| AA_ | Red chestnut, with AAAA being the reddest | Golden palomino |

| At_ | Standard chestnut | Seasonal palomino |

| Aa Aa | Liver chestnut | Chocolate palomino |

This scheme seems perfectly plausible and suggests how palomino breeders might increase their chances of producing the “ideal” golden palomino. Gower also suggests that AAAA horses may be redder than AAAa horses and a better choice for producing golden palominos.

breeding palomino horses

Return to top